From a cozy Christmas market to dramatic storms and floods: all in one December weekend.

Seeing the sea level rise so quickly, to the point where the square was flooded, was a surreal experience that I won't forget in a long time!

Saturday, 5 May 2012

Sunday, 9 October 2011

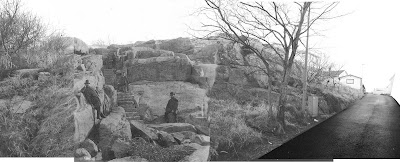

Granite landscapes: Väderöarna

The beautiful, eroded granite in Väderöarna (the Weather Islands), part of Fjällbacka's archipelago. I was beginning to think about the project when I took these photos - the view of the granite framed by the window played on my mind for months.

Monday, 26 September 2011

Granite landscapes: Skärhamn, Tjörn

The beautiful Skärhamn, on the island of Tjörn, Sweden.

I had already explored the island's Watercolour Museum and particularly its artists' studios (pictured) as a precedent, but when I visited the area last summer I also discovered an interesting precedent for the treatment of a granite landscape.

Wooden staircases were playfully scattered around the landscape (perfectly camouflaged with the granite), facilitating the climb to the top of the island without limiting the visitor's choice of routes.

I had already explored the island's Watercolour Museum and particularly its artists' studios (pictured) as a precedent, but when I visited the area last summer I also discovered an interesting precedent for the treatment of a granite landscape.

Wooden staircases were playfully scattered around the landscape (perfectly camouflaged with the granite), facilitating the climb to the top of the island without limiting the visitor's choice of routes.

I took the photographs in July 2010 - I had a great time climbing the rock, sometimes using the stairs... and sometimes not!

Wednesday, 21 September 2011

Precedent: a Norwegian boathouse

Today I saw an interesting building in Dezeen magazine's blog. It is a transformed boathouse in Norway by TYIN tegnestue Architects, and I think it captures some of the qualities I explored in my project: the ruggedness, the closeness to nature, the simple form, the flexible design, the symbolic re-use of old materials, the contemporary interpretation of traditional detailing, the granite, the austerity.

Below are some of the images - for more, see the full post from Dezeen's blog here.

Tuesday, 21 June 2011

A retrospective summary of the project...

Immersions in Memory

Every summer in the Swedish coastal town of Fjällbacka, my mother bathes in the sea early in the morning; a daily ritual of calm immersion with only water, wooden bath-huts and rounded granite boulders as a backdrop, a family tradition with roots in the town’s history. But the seasons transform Fjällbacka from a thriving tourist resort with 25000 visitors in the summer to a deserted ghost town with just 1000 inhabitants in the winter - the perfect crime novel scenario for international best-selling resident Camilla Läckberg.

By delving into the memories of residents and returning summer guests alike, a mosaic of particular visions of the town of Fjällbacka is captured, allowing its layers, character and legacy to be valued and ultimately preserved and enhanced through the project.

On the verge of a significant redevelopment of an abandoned waterfront, the project sits within a context of strong political and economic tensions, with several developers looking to expand on waterfront housing and touristic summer facilities. However, an immersion in the local way of life in November 2009 revealed a strong community with great pride in their culture and history but with very little public space for their events. Social activities and underused spaces were mapped around the town, and events such as the town's weekly sauna were attended. In addition, a bathing event and evening charette were organised and advertised on the local website to discuss development, problems and aspirations. Nostalgia was identified as a dominant symptom of the diminishing population, and discussions were held with locals to find “a new channel for local culture” and discover why "it was better back then". Meetings were also held with developers and council architects, in order to gain an understanding for the different layers that make up the town.

The project looks at the other side of this potential waterfront development by focusing on forgotten public spaces and Fjällbacka’s local heritage, proposing a series of small landscape interventions to frame the local culture and bold landscape. The project proposes the recovery of local symbols and skills to fit within an existing but neglected network, including stonecutting, boathouses and lookouts. Central to the proposal is a new Folkets Hus – an all activity ‘People’s House’, previously lost in the 1960s and found to be missed deeply by Fjällbacka’s residents.

Ultimately, the proposal seeks to regenerate and repair the town’s cultural and social system, reaffirming the local community and mediating between the deeply set contrasts and dualities of Fjällbacka: winter/summer; tourist/local; past/present; timber/granite.

Every summer in the Swedish coastal town of Fjällbacka, my mother bathes in the sea early in the morning; a daily ritual of calm immersion with only water, wooden bath-huts and rounded granite boulders as a backdrop, a family tradition with roots in the town’s history. But the seasons transform Fjällbacka from a thriving tourist resort with 25000 visitors in the summer to a deserted ghost town with just 1000 inhabitants in the winter - the perfect crime novel scenario for international best-selling resident Camilla Läckberg.

By delving into the memories of residents and returning summer guests alike, a mosaic of particular visions of the town of Fjällbacka is captured, allowing its layers, character and legacy to be valued and ultimately preserved and enhanced through the project.

On the verge of a significant redevelopment of an abandoned waterfront, the project sits within a context of strong political and economic tensions, with several developers looking to expand on waterfront housing and touristic summer facilities. However, an immersion in the local way of life in November 2009 revealed a strong community with great pride in their culture and history but with very little public space for their events. Social activities and underused spaces were mapped around the town, and events such as the town's weekly sauna were attended. In addition, a bathing event and evening charette were organised and advertised on the local website to discuss development, problems and aspirations. Nostalgia was identified as a dominant symptom of the diminishing population, and discussions were held with locals to find “a new channel for local culture” and discover why "it was better back then". Meetings were also held with developers and council architects, in order to gain an understanding for the different layers that make up the town.

The project looks at the other side of this potential waterfront development by focusing on forgotten public spaces and Fjällbacka’s local heritage, proposing a series of small landscape interventions to frame the local culture and bold landscape. The project proposes the recovery of local symbols and skills to fit within an existing but neglected network, including stonecutting, boathouses and lookouts. Central to the proposal is a new Folkets Hus – an all activity ‘People’s House’, previously lost in the 1960s and found to be missed deeply by Fjällbacka’s residents.

Ultimately, the proposal seeks to regenerate and repair the town’s cultural and social system, reaffirming the local community and mediating between the deeply set contrasts and dualities of Fjällbacka: winter/summer; tourist/local; past/present; timber/granite.

Friday, 23 July 2010

A journey through the project, inspired by Camilla Läckberg

As they left the church on the bitter January morning of the funeral, they walked silently together across the old cemetery, wrapping their coats tighter to fight the biting wind. As they slowly made their way up the embedded steps in the mountain she felt the summer memories of climbing islands come flooding back – as a child she had always wanted to climb to the highest point of whatever island she was on, trying to identify the different lookouts and lighthouses in the archipelago.

As they reached the new lookout they paused to catch their breath. In the summer a crowd of tourists would always be waiting to climb up its stairs, which reminded of Badholmen’s diving tower, but today they were alone. As they entered the warm timber enclosure they were met by the stunning, frozen view. Directly ahead of them across the thick ice they could see the lookout on the island of Kråkholmen.

They descended the mountain and entered the granite enclosure of the Folkets Hus. She could still remember the time before Badis was demolished – everyone could. The building’s footprint could still be made out between the drystone walls now, its distinctive curve cutting through the rock. It had taken the local stonecutters weeks to pave and wall the granite garden, and their craftsmanship had resulted in an array of granite forms and strata, from boulders to cobbles. In spring the regional stonecutting cooperative always brought their trainees here, and new granite sculptures and benches seemed to emerge every year.

They entered the building through a narrow wooden enclosure, and after hanging their coats up and taking their shoes off, arrived at the main volume against the back of the granite fireplace. The low winter light entered the smaller meeting area – it looked so different from the summer, when it served as a café, always full of sailing tourists browsing the Internet on their laptops. As they passed the kitchen they heard the sound of plates, and she remembered that the book club had their meeting here today.

They slowed down as they entered the main space and were met by the steep rock suggesting its presence behind the deep walls. Last week she had watched the snow build and melt away down the carved channels outside, but today the low winter light bathed the roof and floor inside, and she felt the cold leaving her body. They paused to admire the archipelago horizon beyond the heavy granite stage – she personally preferred this view to that of summer, when the stage faced the outside and the local performers got to enjoy the stunning view.

Her father had particularly enjoyed extending his evening walks past the building, as the light from within played on the rock. But she preferred her morning walks, and often came here with a book early on Saturdays, when the sun would highlight the colours of the granite outside – if she was early enough, she could catch the first rays trickling into the space. She found comfort in the constant connection to the landscape outside, and the deep wall strangely reminded her of her summer morning dips, when she would sit on a bench and lean against the uneven timber wall in her bathrobe.

They turned and made their way back out into the cold. She stopped at the door to look out – through the window in the drystone wall she could see the lookout on Kråkholmen. She stepped out of the light, timber building and back onto the hard granite paving. It always amazed her how many people fit in this walled space during the summer auctions, dances and exhibitions. Now they were alone.

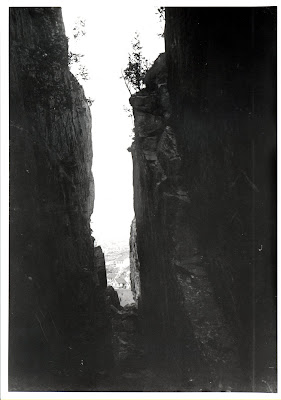

They turned around one of the walls and descended through the narrow stair to the waterfront. In the summer it was a cool, shady transition between the mountain and the open, glittering water, but now the steep walls protected her from the chilling wind. Straight ahead, in the distance, she could see the overwhelmingly steep walls of Kungsklyftan – the King’s Cleft.

As they emerged by the water, they saw the boathouses. Their charred wood façades reminded her of the fire that destroyed Fjällbacka’s waterfront in 1928. Inside one of them, the lights were on – it was probably one of the local artists who she knew used it as studio space. She looked back at the open stage and briefly remembered watching Casablanca here on a balmy summer evening. She then glanced at the ice she was about to walk on, and couldn’t believe it was the same water she had bathed in only a few months ago.

They stepped off the pier and onto the ice, and walked towards the cemetery on Kråkholmen. She always enjoyed the feeling that the islands were secretly accessible to them during exceptionally cold winters like this one, and today was no exception. The funeral had been stirring, but the walk through the granite landscape and out to the cemetery was refreshing. As they reached the island she couldn’t fight the usual urge to climb to the highest point, and soon found the lookout. She climbed up its familiar rhythm of steps and paused to looked back the way she’d come from.

Fjällbacka looked quiet, peaceful and bathed in a cold light – drastically different from the summer sounds of seagulls, sailing masts and swarms of people soaking up the evening sun. She couldn’t decide which view she liked best.

Monday, 21 June 2010

Saturday, 5 June 2010

Linking to an existing cultural and social network

A new Folkets Hus has the potential to link to the existing institutions of the town, including the archive, library, hotels and restaurants. Together, they act as a network suitable to meet the needs of a range of programmes from exhibitions to conferences.

A new Folkets Hus has the potential to link to the existing institutions of the town, including the archive, library, hotels and restaurants. Together, they act as a network suitable to meet the needs of a range of programmes from exhibitions to conferences.

Some of the new spaces proposed - such as the boathouses - could be rented out to generate income for the Folkets Hus and finance exhibitions and performances.

Friday, 4 June 2010

Folkets Hus - a timber enclosure relating to granite horizons

The proposed Folkets Hus - light plays a key role within the building, as does the granite stage, allowed to come through from the ground below and serving as an anchor in the seasons.

The proposed Folkets Hus - light plays a key role within the building, as does the granite stage, allowed to come through from the ground below and serving as an anchor in the seasons.

A window seat within the wall allows views of the morning light playing on the rock outside, through the board on board timber cladding. This cladding is a reinterpretation of the local vernacular, adapted to include a seat and glazing. Below, an image taken at Badholmen.

Folkets Hus - a collision of past elements

The proposal for Folkets Hus takes its size from the old footprint of Badis, carved into the granite, the old Folkets Hus and the church. The church becomes a clear precedent in terms of size, being the one space in Fjällbacka which at key moments accommodates the whole town.

A network of interventions to enhance local identity

|

Through the introduction of new landscaped routes, boathouses, lookouts, cemetery, stage and Folkets Hus, the landscape is framed and protected from other development. All the proposed elements are reinterpretations of local symbols rather than unfamiliar, new ideas, and embrace Fjällbacka's physical and cultural heritage.

The network of proposals seeks to "provide a new channel for local history and culture", a need highlighted by the locals during the November trip.

The dual lookouts and cemeteries serve to visually link the mountain of Kvarnberget to the island of Kråkholmen, extending the perceived public space to the sea and archipelago.

Timber and granite - proposal concept

The relationship between granite and timber was identified as a key theme early in the project explorations, and has become a vital part of the proposal.

The heritage of the stonecutters is reinforced through different granite strata - drystone walls, granite paving, cuts in the rock and monolithic boulders highlight the local skills of the area and the permanent quality of the landscape.

Light timber inserts with a stage-like quality sit delicately within this granite landscape, and provide inhabited warm spaces for the winter.

Badis is identified as the epitome of summer and tourism, and is replaced by a Folkets Hus, a year-round symbol of local identity.

A vertical journey through granite

A new stair is proposed to link the waterfront to the mountain of Kvarnberget. This granite stair, enclosed by an existing drystone wall, has a narrow, vertical quality reminiscent of the 'King's Cleft', Kungsklyftan, directly in line with the stair.

In the summer, this stair would provide a cool, shady transition between the sunny, bustling waterfront and the granite mountain; in the winter, a shelter from the cold, bitter wind.

Further steps carved into the mountain take the visitor through the mountain and up to the lookout on the highest point.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)